How A Museum Visit Changed How I View The World

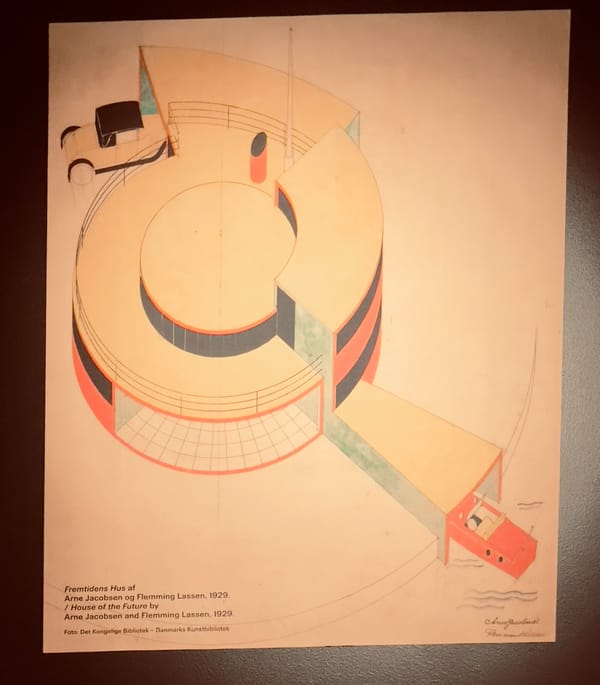

If you've ever been to the Design Museum Danmark in Copenhagen, you don't walk through a gallery – you walk through time. The exhibits lead you through the history of human design and ingenuity. If you look close enough, you can hear the story they tell. Because design isn't just a solution poured into form. Design shows what people around the time of its creation valued. Nothing shows this better than the "table room": you walk past an assortment of tables, every single one made centuries apart.

What becomes apparent is that design over the years has become simpler. The furniture from earlier centuries is beautiful and detailed. It is the messenger of the values from the people back then, and it screams that more is better. When you know the situation these people faced back then, it's clear why they thought this way. While in our modern times we struggle more with being overweight than starvation, it was the opposite for these people: famine followed them every step of the way. If you had enough food to feed your loved ones, you were considered to be on the upper echelon of human society. That's why even the furniture screams abundance. The ability to provide in excess was valued to the highest degree.

In comparison, here’s a typical modern table:

When I look at both tables, the second one resonates much more with me. But that's probably because I'm influenced by the times we live in. In comparison to our ancestors, who might've resonated with the Rococo table much more, we're not in awe of furniture that signals the ability to keep your loved ones fed. That's because our basic needs are not just met—they're oversupplied. In our age of overabundance, less seems to be more. In simplicity lies power – which makes simplicity one of the antidotes to the perils of our modern age.

Once you start looking for simplicity, you realize that some of the things you thought were complex are eerily simple. This is also true for one of my favorite topics: business models.

Simple business models may transform into more complex systems over time, but the best ones remain simple. Amazon started as an online bookstore. A quick look at Amazon's website today reveals the behemoth that it has become. But the core business models behind these products are still simple. No matter what you order on Amazon, the principle stays the same: you give Amazon money for the product you want, and they use their supplier and delivery network to get that product to your home. Amazon Web Services adds to Amazon's complex product palette, but its business model is as simple as the first one: renting out computing power and digital services over the internet.

After doing this for a while, you realize something: cutting away at complexity is fun. But it can become addictive. If you simplify something too much, you might remove an integral part, and the whole system breaks down. Just imagine if we wanted to simplify the design of the Rococo table and decided that, with its layout, it would be simpler to have only three legs. The whole construction would fall – and we'd have created a simpler, very crappy table. That's why, if you want to simplify something, you need to understand it first.

Richard Feynman was one of the greatest explainers who ever lived. His system for understanding and teaching all kinds of different topics boils down to one principle: simplicity.

Using complex words to explain a topic is the easy way. What's difficult is explaining it in the simplest terms possible.

For example, in computer science there's a principle called "abstraction". In its essence, abstraction shows the user only what he or she needs to know. Here's an obnoxious intellectual version compared to a simple version:

Abstraction constitutes hierarchical stratifications of conceptual encapsulation that obfuscate implementational minutiae through systematic information hiding. This metacognitive framework enables compositional interfaces presenting simplified semantic surfaces while occluding underlying mechanistic complexity. The abstraction barrier functions as a cognitive firewall, delineating ontological boundaries between computational representation layers.

I'm not even a computer, and my circuits fried reading that.

Here is the same core message, but in simple language:

Abstraction is like having a simple button that does complicated work behind the scenes. When you press "volume up" on your TV remote, you don't need to know about all the tiny circuits inside - you just get louder sound. Computers work the same way: simple controls hide all the hard stuff so you can focus on what you actually want to do.

The first version might sound more sophisticated, but it’s actually much easier to write. Gunslinging jargon misses the target, since next to nobody understands what you're saying. In comparison, the second version is much simpler, but it's much more difficult to write, because you can only use simple language.

The principle of simplicity is applicable in an area that most wouldn’t think of at first. Simplicity can also serve as a compass for a better life.

Auditing your life can turn it into a museum of sorts. There are different exhibits from different times that make up your past and present. Maybe you want to see some exhibits again in the future. With some, you're happy to leave them in the past. But you will eventually reach your equivalent of the table room. Then you might realize that sometimes – just like the Rococo table – you use ornaments you think you need, but actually don't: accolades, a fancy car, a fake smile. Showing people a version of you that you think they'll respect. But too many ornaments bog you down and obscure the authentic version of you. That's why, by simplifying your life, you might find the life that is simply yours.